Disenfranchised Grief #1

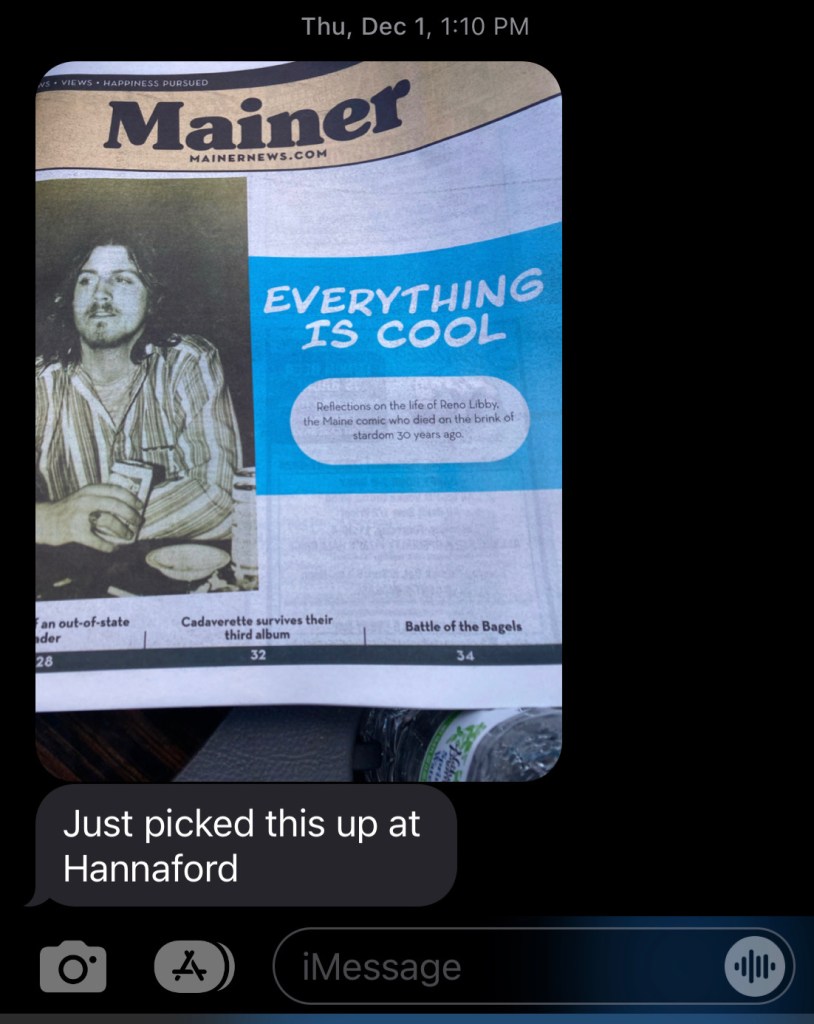

Yesterday, a friend texted me the cover of the recent issue of Mainer because there is a picture of Reno on it. They had written an article about him: “Everything Is Cool: Reflections on the life of Reno Libby, the Maine comic who died on the brink of stardom 30 years ago.” Reno was my boyfriend in those days, and then my friend. I texted my friend back that I didn’t think I could read the article, yet.

We met at a dive in the Old Port called Amigos, where he played pool. He was the best in town. (Years after he died I was playing pool and realized in a flash that he had taught me to hold the pool cue wrong, on purpose.) We made eyes at each other for a few nights, and were together from the moment he stopped by my table to ask if I wanted to be his partner at pool. I said, “I suck.” He said, “All right. But that’s not what I asked you.”

At last call, he asked to take me to dinner the next day. Just a sweetness, no barfly banter. His roomie and mine horned in on our plan and both insisted on joining us. His had a crush on mine, and mine wanted a free meal. So the four of us met up somewhere with hard plasticky booths and fluorescent lighting, maybe Chinese, and Reno told stories over dinner that made me laugh till I was helpless, mascara everywhere.

It was surreal to see him standing there in my living room, that first full day we spent together, when I still wasn’t situated with what he looked like in the sunlight. He seemed a little feral and I was a little dazed. But integration was swift. I was all in. We went to his place and picked up his dog, Duke, dorked around town, showed back up at Amigos together. I got used to the smokey smell of his beard. He moved in.

At the end of things, he had started spending a lot of time away from home, just getting lost. I didn’t know where he was going. I hated finding him passed out in the living room, soaking in spilled beer. I remember standing over him holding my breath, waiting for him to breath because I wasn’t sure he would. He’d take my car and stay gone till I was frantic. And lonely. If he was doing heroin then, I wouldn’t have been able to interpret what I was seeing. He didn’t bring it home. One night after he had been MIA, I asked him if he’d give up our relationship to keep partying like a maniac. He said, yes, he guessed he would. I reacted like a twin maniac, sweeping all the clutter off our dresser onto the floor. I’d asked a question I truly didn’t want the answer to, and there was no equivocation in that answer.

The hard, shitty information he gave me that night lightened things up around the house, though. It wasn’t my place to tell him anything, anymore. We continued to live together and our breakup was lingering and a little messy, but never contentious. I remember that Ren and Stimpy had come out around then, and we’d watch it together, leaning into each other laughing, even as we disentangled. We eventually moved out of the place we shared. I went to Old Orchard. He still called me. He called to tell me when he won the Tonight Show thing.

When Reno died, I was visiting my mother in Florida for the holidays. While I was there, my dad called me from Maine to tell me that Reno’s mom had been calling his office. When he finally connected with her, she was so hysterical he couldn’t make out what she was telling him, but it sounded to him like Reno’s father had died. And why wouldn’t she call my father about it? She had to be beside herself. My dad’s a lawyer, and maybe she needed help with something. (I realize that she was trying to reach me.) I didn’t question my father’s interpretation. I never wondered if it could have been Reno who died. There wasn’t a whisper of that possibility in my mind to reject. I didn’t know what he was doing.

When I returned from Florida after the new year, I went straight from the airport to a restaurant in the Old Port where my friend, Johnny, was working. Johnny came out of the kitchen to greet me and immediately asked if I had heard about Reno. I remember that inner drop, the feeling of my equilibrium shifting at the odd question because… why would Johnny know about Reno’s dad? I said, “Yeah, his dad died.”

Johnny said, “Ilse… No.”

Reno’s funeral was already over by the time I found out. There was nothing left of him, like he evaporated. Nowhere for me to go with it. I wasn’t his girlfriend anymore, so no one cared that I’d lost him. It wasn’t my place to freak out or grieve publicly. His little brother came to visit me a few times, though. He’d show up, fully shattered, sit next to me on my futon, bereft and half mad with grief.

A couple of years later, I went half mad myself. I was living alone, in another state, and found myself unmoored by this grief and heartbreak that I didn’t feel a right to. Maybe being alone and far away made the space for it, and the sudden, stupefying weight of it rolled in like a sneaker wave. I even sought out a psychic, which I knew was so dumb, but I would have rather been told a lie than keep spinning out there with nothing. The psychic told me that Reno was around, but he was busy singing. I mean, it sounds right.

These days, I hold space with people who are walking with grief. When I’m in it myself, I am as messy and heartbroken as anyone, though it helps to have words for what I’m experiencing. It doesn’t hurt less, but having the language allows me to name and hold my own grief with compassion. I recognize now that I was navigating “disenfranchised grief” — a loss that leaves the bereaved feeling their suffering is illegitimate, invalid, or overblown. Often, it’s a grief that’s denied mourning, the embrace of community. No one wonders if you’re OK.

Seeing Reno’s picture on my phone yesterday swung open a door that let a ragged grief slip in around my chest. I remembered that old picture, taken before I knew him. When I saw his face and the title of the article, I felt the estrangement fresh again, and added 30 years distance. I raised a whole child into a grown up with a full time job in that time. But here I am, aching just the same, and still on the outside looking in. No one remembered I was there. That I was the girlfriend in the jokes he told those first open mic nights. No one knows he was here, sleeping beside me in this room on the lake where I’m writing this.

No one looked me up to ask if he’d crinkle his nose and look straight into your eyes when he laughed, because he only ever laughed with you. Does anyone remember his Zigzag man tattoo and those gross, flappy, beat up red shoes he thought were his dress shoes (it was wrong of me to hide them). How he carried Visine everywhere, not because he was stoned (he was), but because he had burned his eyes on the snow, skiing without sunglasses, and they wouldn’t tear up anymore. How he’d astral project, and tell me things he should not have known unless he had somehow been there.

One night, he went to bed before me while I stayed up late catching up with a friend who was visiting from out of state (actually, my roomie from that first date, who had since moved on). She and I took a boozy, midnight walk around the neighborhood, stopping to sit on the steps of a nearby church. When I crawled into bed next to Reno later, he woke up and told me all about my walk, about everything my friend and I talked about, about the church steps. He said he hadn’t meant to, but popped out of his body as he was falling asleep and followed me. He seemed to keep one foot in that unknowable plane and told me how he’d talk to his dead friends there. I knew he wasn’t entirely earthbound.

Does anyone know that when he was a little kid, he was celebrated in the paper for being the only one in town to figure out that the loud, mysterious plague that descended on Waterville was a swarm of newly hatched 17 year cicadas. His mom showed me the newspaper article while we perused Libby family photo albums on her coffee table. Maybe that’s when I first saw the picture that appears on the Mainer cover.

I wonder if anyone else remembers that he idolized Sam Cooke and Harry Chapin along with John Prine? A pantheon of storytellers that should include him. He should be there. Can anyone else still hear Reno telling Duke to “Stay close.” I say that to my dogs, now, too, and think of Reno every single time it comes out of my mouth. They don’t know what it means.

When the Mainer article finally appeared online, I could only squint at it at first. It was a bit like looking straight at the sun. I opened and closed it a few times, absorbing it in bits and pieces. One of those times, I alighted on a detail that shifted my footing and the entire landscape in a blink. I had been outside; now I was inside, but the effect was the opposite of disorienting. It was integrating: Reno had a copy of A Prayer for Owen Meany on his table when he died. Reno’s brother, Michael, remembers that Reno picked it up after someone had mentioned it to him at a party. I believe it, but there’s more. When Reno and I were together, John Irving was in my personal pantheon of storytellers. I was particularly smitten with Owen Meany. Reno knew. I shared Irving with him the way he shared John Prine with me. Learning he had this book with him when he died is like seeing a star twinkle into focus in a black sky, being touched by a light that took 30 years to reach me.

This was a wonderful article to read in the Bollars I just brought home. It left me knowing Reno in an intimate positive way. Better than the original. Thanks

LikeLike

Thank you so much, John. I really appreciate hearing that.

LikeLike

Sorrow floats ❤️🩹

LikeLike

I haven’t heard that phrase in so long. Thank you.

LikeLike

I just read this in the Bollard. Very touching. I had also read Everything is Cool in the Mainer and was moved to a mix of curiosity, attachment, and sadness. I did not know Reno, but Amigos and several other seductive local establishments were my hangouts in the mid 70s before I realized I needed to live in the country. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Brian. Yeah, I share those feelings… And those places definitely had a vibe. It was fun, but the country suits me much better now too.

LikeLike

I just read your piece in Mainer, err, The Bollard. It was really touching. I never met him, but I now feel like I know you both. I just put a hold on a copy of A Prayer for Owen Meany from the library, which I look forward to picking up.

LikeLike

Thank you, Patrick. I’m happy that people are remembering Reno and meeting him for the first time. He was a light. I really hope you enjoy Owen Meany. I think I am going to re-read it. It has been so long.

LikeLike

This piece of writing really has soul. Thanks for sharing your story and your gift.

LikeLike

Thank you, Slade. I appreciate that so much.

LikeLike

Just read your article in the Bollard and I was overwhelmed, absolutely beautiful. The touch about Owen Meany killed me at the end, I also have a John Irving connection to a special person of my past and a copy still on my nightstand. Thank you. I also can remember that Portland lifestyle from the 90s that you re-create so well.

LikeLike

Hi Jennifer, Thank you! That Owen Meany detail did all the work for me. I’m so grateful Michael found his recollection of the book significant enough to tell. I love hearing about your Irving connection! My sister also shared her own with me, and noted that there is something very John Irving about all this.

LikeLike